This post obviously contains spoilers about games in the Mass Effect series. If you haven’t played them, close the window and go do that first.

It’s been over two years since EA released BioWare’s third installment of the Mass Effect video game series, and about the same amount of time has passed since the Internet was filled with riotous uproar over the ending. Like any compelling piece of art, there are countless forum posts, blogs, and rambling fan theories floating around about the game’s deeper meanings and symbolism, and how good or bad it was. In Mass Effect 3’s case, the response to the original ending was overwhelmingly negative for a variety of reasons, the chief of them being the apparent discord between the different endings and the player’s decisions in the last three games. And in a series hailed as– and based heavily on– player choice, this did not sit well with a lot of fans. BioWare later released an update, the purpose of which was to further explain the meaning of the endings and to show why they weren’t so bad. But this was “too little, too late” for many players. Accepting failure is a difficult thing for many people to swallow– creators and consumers alike– especially the failure of “their” protagonist in a story they are passionate about; and I think it’s safe to say many fans felt betrayed because all of the options for the ending felt like a failure in one way or another. How could we let the synthetics win?

With more and more info about what may happen with the next Mass Effect game cropping up online, I wanted to give my own perspective on the trilogy’s ending. I personally loved the games, although I prefer the first over the other two (to me it harkened back to the good old days of KOTOR, while the other two strayed farther from being anything close to an RPG with action elements, and more of a 3rd person action shooter with some RPG elements). The games are beautiful, the overarching story is Epic (and coming from a Classicist, that actually means something– note the capital E), and the character development is compelling. I loved almost every minute of playing those games. In order to have a fresher sense of the game, I went back and played the last few missions before writing this, and took some screenshots. (aside– why does Origin not have a built in screen shot function like Steam by this point?). I had to use my own screen shots because I wanted it to be my Shepard.

I started with the last few missions on Earth. Not really remembering the controls, I fumbled around a lot trying to deal with these Banshees, who, by the way, are completely horrifying. Not only are they grotesque in a manner that Poe would love to describe– they also fill the air with an atmosphere of what Lovecraft might call “abject horror.”

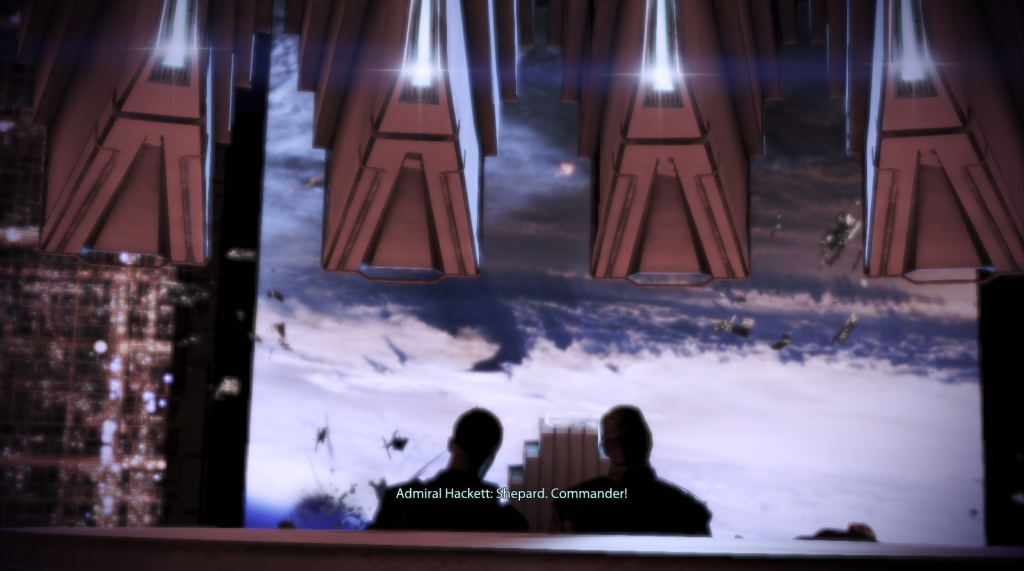

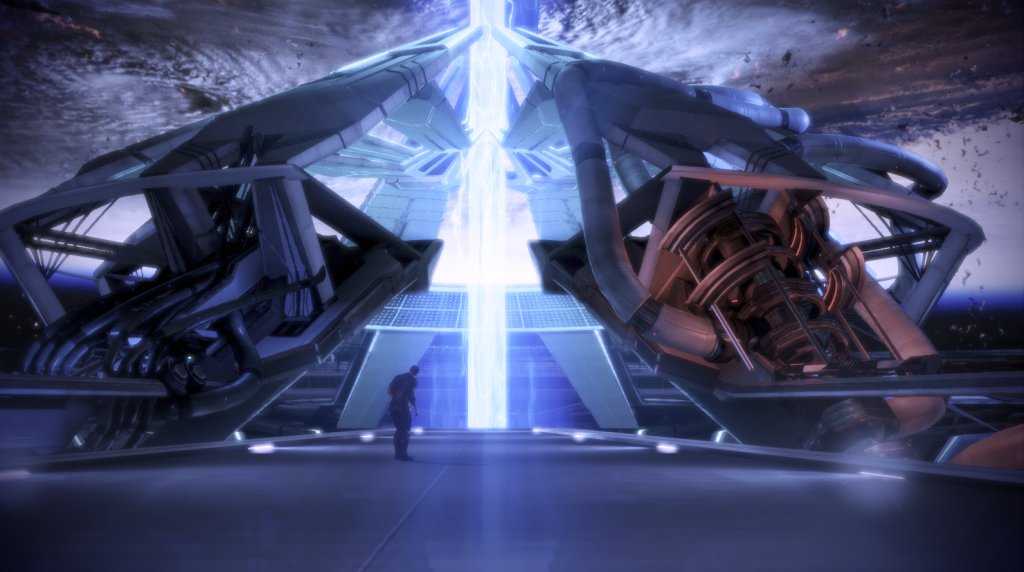

After humbly moving the difficulty down from “normal” to “narrative,” I continued with the story. Once the battle with the Banshees is complete, there is hardly any actual gameplay left– the remainder being primarily cutscenes and a “fight” with one indoctrinated Turian monster. And that’s OK, and it works in such a beautiful and story-centric game. For example, before entering the Crucible, we are faced with this awful (that is, full of awe) scene:

The atmosphere is there. The emotion is there. And I was ready to deal with the Reapers.

Once on the “ship”, we see Shepard, our protagonist, very alone, in a moment of great emotion. And what an interesting character he (or she) is. Not only does the character become “ours” over the course of the three games as we customize and give him (or her) a personality based on our choices, but Commander Shepard is a prime example of a modern day Epic Hero (but that’s a post for another day). I felt like I could take on the entire enemy fleet single-handedly.

Now it’s right about here where I think the developers could have ended the story in a beautiful way. There may have been just as much backlash, but I think this ending would have been far more fitting. After dealing with the Illusive Man, Shepard and Anderson sit down and have a moment:

And that’s it. End it there. Roll the credits. Our final scene of this beautiful game should be these two men, both gravely injured, gazing at the final moments of their home planet from a space station– beholding the end of the world and the human race as they know it. Knowing they failed in their mission to stop the Reapers’ annihilation of organic life, Shepard and Anderson sit in silence, ignoring pleas from their radios. Awestruck by the scene, tired from the constant struggle, the two accept their fate, slowly bleeding out as they watch the show. They have failed their mission– and that’s OK. Because failure can be beautiful. And getting a listener or viewer or reader or player to understand that– it’s not easy. Most people want the hero to kill the bad guy and get the girl and live happily ever after.

Instead of leaving it there, though, Shepard leaves Anderson’s corpse as he ascends to another platform (with a lot of imagery here too, that will be discussed in a future post). I forget which ending I picked the first time I played, but it doesn’t matter. I wanted to end the game with something as close to the tragedy I envisioned above as I could. When talking with the Crucible AI Child Thing, if you are persistent enough you can simply choose not to act (and that alone deserves its own post). The whole dialog tree is the AI kid enticing you to pick something, letting slip that doing nothing would ensure the destruction of humanity and all advanced organic life. And that’s exactly what I chose. Because even the best heroes fail. And that’s OK.

P.S. The only way my version of the ending could have been more perfect is if it were Garrus instead of Anderson.